Back in 1967 when Canada was still engulfed in the optimistic promises of the early 1960s and the country was celebrating its centenary with vibrant activities such as Expo '67, Canadian National decided to create a new named passenger trains to link Montréal to the Atlantic. That unusual train would be christened "Cabot" in honor of a famous Italian explorer Giovanni Caboto (1450-1498) who worked for the British Crown. From discovering the "New" World to discovering "Terre des Hommes", it wasn't hard to make the link.

As you know, I generally don't care about passenger service. I barely never experienced passenger trains in Quebec during my lifetime except about 5 or 6 times on Via Rail, taking the first Tortillard in 1985 when I was a toddler, seeing the second Tortillard from a few miles away and riding three times touristic trains which I found boring as can be, except for a nice cab rid on JMG1 back in the early 2000s. I have a much more strong link with Belgian interurban trains on which I rode extensively when I was studying there, wasting entire weekend days running around the country to try every line I could while sightseeing. I also have a much deeper connection with Japanese railways of all kind, which were a great fun to ride too. Count in that a short but fantastic (from my point of view) run on a preserved C62 - the epic locomotive pulling Leiji Matsumoto's famous Galaxy Express 999 - at Kyoto Railway Museum.

That said, it doesn't mean I don't care about North American passenger trains, but simply they don't make my heart beat that much and as much as I can say, VIA Rail will always be a disguised bankcruptcy scheme playing with trains. However, I like mixed trains and when an unusual motive power pull a passenger train, my interest is somewhat rekindled.

Years ago, Jérôme shared a picture shot in Drummondville on July 4th, 1967 by Bill Linley and depicting the "Cabot". Under normal circumstances, I wouldn't have cared, but this train was pulled by a pair of C424 and there was a steam generator. I was hooked. In Bill's words:

Canadian National's newest name train, the Cabot, was just five weeks into its service life when I photographed it in Drummondville, Quebec, 62 miles east of Montreal on Tuesday, July 4, 1967. It began on Thursday, June 1, 1967, as a through 966-mile service from Sydney, Nova Scotia via Edmundston, New Brunswick to Montreal, Quebec. This route was the main route for freight to the Maritimes. Local services on the line that CN discontinued included a tri-weekly local from Moncton to Edmundston. They also cut similarly scheduled mixed trains that required an overnight stay at the intermediate division point of Monk if travelling between Edmundston and Joffre, the freight yard near Quebec City.

CN anticipated large travel volumes for Centennial Year events, notably Expo 67, the Worlds Fair in Montreal. Their new train reduced pressure on the Halifax - Montreal Ocean and Scotian services by offering a speedier, direct service for passengers from Newfoundland and eastern Nova Scotia. Train 18 left Montreal daily at 6.45 p.m. and arrived in Sydney at 9.15 p.m. the next day, easily connecting with the Newfoundland 'Night Boat' in North Sydney. In Nova Scotia, CN discontinued the overnight Halifax - Sydney conventional train on May 31, 1967, and added a through Sunday Railiner service.

The launch also saw the discontinuance of similarly numbered trains 18 and 19, the remnant of the old Maritime Express on the Moncton - Montreal route via Campbellton, New Brunswick. Local stops between Campbellton and Charny were then served by RDC's on Trains 618 and 619. On Wednesday, May 31, CN introduced another through coach, sleeping and dining car service to Gaspe on Trains 118 and 119 from a connection with the Montreal - Campbellton, Chaleur, Trains 16 and 17, at Matapedia, Quebec. At the same time, CN cut off Matapedia - Gaspe RDC's Trains 616 - 617 and except Sunday Mixed Trains 246 - 245.

The Cabot was a lengthy train. It included two coaches with reservations required for distances over 160 miles, unreserved coach(es), diner, lounge, coach-lounge, cafe car and four sleepers for the entire run. An Island series, 8 section 4 bedroom sleeper served Montreal - Edmundston and, an E-series 4 section, 8 duplex roomette, 4 double bedroom car ran between Montreal and Moncton.

The Cabot featured unusual motive power as CN assigned a pair of MLW C-424s and a steam generator car between Montreal and Moncton. They had 75 mph gearing, which was appropriate to both flat running and the curvy and hilly former National Transcontinental line through Edmundston. A pair of RS-18s often provided the power from Moncton to Sydney. However, the late James Hardie's photographs at Glen Bard show a pair of MLW cab units charging up the grade with 14 cars in tow. In this picture, MLW built MR-24b 3219 stands ready to depart Drummondville at 8:11 p.m. on the Fourth of July. MLW delivered 3219 in the summer of 1966. CN leased many of its 41 C-424s in the U.S. and Mexico. When MLW purchased 3219 on Tuesday, January 26, 1984, I think that they sold it to the NdeM.

An indication that the new Cabot was a success came in October 1967 when the premier train, the Ocean, added through Sydney cars at Truro and began to operate via Edmundston. The following summer season from late June through early September, the Cabot again ran as a through, separate train from Sydney but serving Campbellton while the Ocean continued to run via Edmundston. This seasonal pattern continued until Wednesday, January 7, 1970, when the Ocean once again travelled via Campbellton. From then until the end of though cars in late October 1979, the Scotian handled the cars west of Truro.

As you can see, it was an unusual train. In a recent discussion with Bill, we tried to visualize the consist to see how it looked and what were the exact cars used. Interestingly enough, while the train may have looked somewhat homogeneous, there were a few oddities including an old clerestory heavyweight 12-1 dormette car and several sleepers acquired by CN from MEC, BAR and NYC. There was also a rare Rock Island sleeper still in its old paint scheme purchased by CN the same year to face the increased demand. Pullman Standard cars of various origin and built date created a common yet somewhat varied look.

So, can this train be modelled? The short answer is yes, but it will need a lot of modeller's license and a few repaint. I'm not that much concerned of replicating exactly each cars with the correct windows, but I still would like something that is close enough to be plausible. Also, good quality cars would be required. Fortunately, by assembling together Rapido and Walthers cars, it isn't impossible to make a decent consist.

I already have a pair of DCC sound Atlas CN C424 in the correct paint scheme. Rapido will soon re-release their GMD steam generator, a few repainted True Line Trains 8-hatch reefers with express trucks would also do the job. Walthers produced in the past a decent 12-1 heavyweight sleeper perfect for the lower class passengers and if you pick various cars from Rapido and Walthers, you should be able to find a decent prototype for must cars. Even the Rock Island car can be purchased RTR. Many serious passenger modellers will cringe at my attempt, but bear in mind I'm a freight car enthusiast and I can perfectly live with the 3 foot rule if it applies to passenger trains... something I wouldn't allow with freight!

However, you must keep in mind the Cabot was a long train, very long. More than 16 feet in HO. In total, it would be at least 17 cars long! Given must cars are now discontinued and their prices have skyrocketed, I consider such a train would cost me almost $1400 even if I take into account I already own 2 locomotives and 5 cars. Not a small investment.

|

| How I would replicate the Cabot |

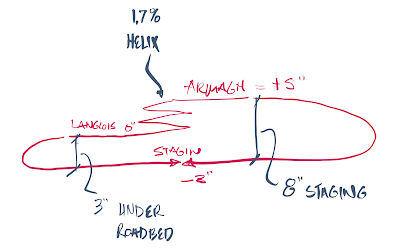

Would it be interesting to run such a train on the Armagh Subdivision and staged meets? Probably, but I think this is the kind of project you slowly build, adding cars as possible over a long period of time, until you complete the consist. Maybe an interesting aspect of the Cabot is it used basic cars that can be assembled in smaller trains that did run over the subdivision. It makes the investment less whimsical that way.