|

| A steam freight train in Hokkaido, circa 1968 |

As Sanstead is coming to an end, it’s now time to think about Monk. A series of discussions with Chris Mears took us to Hokkaido during the last years of steam operation in Japan in the late 1960s and early 1970s. We explored ways to create a series of cameo scenes linked together on a scenic N scale layout using Kato components. The goal was not to build something or to plan for a real layout, but to play with a lesser known prototype which share a lot of Canadian-like feature such as topography, rivers, vegetation and mountains. Sure enough, steam era in rural Japan is an impressive thing. It merges together state of the art late steamers with narrow gauge and layout-friendly features such as steep grades, scenic bridges and tunnels. The locomotives of that era are themselves marvels of engineering; the Japanese having pushed to the limit what could be done with narrow gauge. Fair enough, having seen these brutish 4-6-2, 4-6-4, 2-8-2 and 2-8-4 with my very own eyes, I can tell you can’t distinguish them from their standard gauge brethren if you don’t start to look closely at the rail spacing. In some way, they heavily borrow from big American steamers while keeping specifically Japanese details that puts them, in my mind, in a similar category than Canadian steamers. The vocabulary is the same, but the accent is different if I could say.

|

| A train running in a valley in Hokkaido |

|

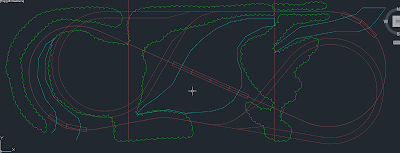

| Compressing a river horizontally... |

|

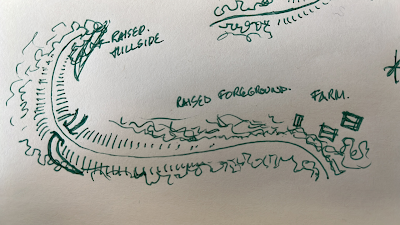

| A study in elevation |

Such a layout doesn’t need to replicate complex operations. As is fashionable with Japanese layout, you railfan your N scale trains on a generally quite simple track plan. In my eyes, it’s an excuse to see nice trains crossing through a beautiful landscape. For this reason, I can easily imagine a single track mainline with two hidden returning loops acting like shadow stations. The visible part of the layout is depicting a river valley and several bridges and tunnels dividing 3 similar but differently framed scenes. It may sound gimmicky, but when you study rural lines in Hokkaido, you quickly discover than in some areas, it was common to find 4 major bridges per miles. In that regard, the old Shiranuka Line provides inspiration beyond your wildest dreams.

|

| A single mainline layout with hidden returning loops |

That said, as much as I love late Japanese steam and find Kato N scale locomotives exquisite and reliable, it is very unlikely I will commit to that. However, all these themes of framing scenes about large steamers traveling a rural landscape with some staging are in fact nothing more than what Monk is all about. Once again, good design is universal and can serve several prototypes over continents.

|

| Returning loops in dashed lines |

One thing I’ve liked with the Japanese layout is the returning loops used as staging. Many Europeans (and Americans) use that trick to create a sense of going somewhere. It is particularly useful when you want to model traffic between two division points without having to model them or fiddle with trains. The automated reversing ensure traffic moves in both directions. It’s also easy to automate and control trains in a compelling way.

In the case of Monk, there are two options. The first one is to replace my current staging with two loops under the upper level (Armagh). I once explored that idea with Chris Mears and while it’s extremely elegant on paper, it’s a nightmare to build and to maintain. Accessibility is appalling and hiding tack with scenery is a recipe for disaster. It’s not that different from what I have built until now. Trevor Marshall advised me to stay away from hidden staging and tracks that cannot be maintained properly. I’m not sure I listened to him even if I knew he was right. Current maintenance issues on Murray Bay Subdivision do remind me how frustrating dealing with electrical issues is. Mind you, all tracks all accessible and visible on that layout!

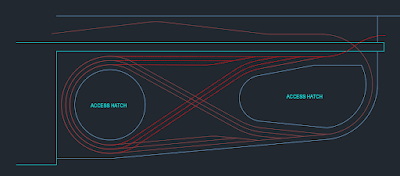

Enters option 2, which consist in building the loops outside the room. Not something I was eager to do, but now I’m seeing more and more value to that. Basically, two loops would be built on a table on top of each other. The yard throats would be installed in such a way they don’t overlap, which would make them easier to monitor, repair or maintain in the future.

This option would remove all hidden trackage from the layout which is a good start. But it would also get rid of superposed trackage in some area, eliminating vertical clearance issues. Another good point is that scenery will be much more easier to create since there will be no need for access hatches and other clumsy and annoying contraptions. Also, Armagh scene would be narrower with the elimination of the stating yard that was located being it. More space in the room isn’t a bad proposition.

Finally, the swing gate will only have to deal with a single track and no grade, which will make track alignment easier and less prone to seasonal dilation. Yes, this is a serious issue to keep in my and I wouldn’t mind making the bridge even more simpler.

That said, it means that almost everything I built last year is now completely useless. Is it a big issue? Not really. I’ve learned a great deal about model railroading in the last 18 months, much more than I could have ever predicted. My goals are the same, but I have more sophisticated tools to reach them and it would be foolish to go forward with premises that no longer makes sense and show their limitations.

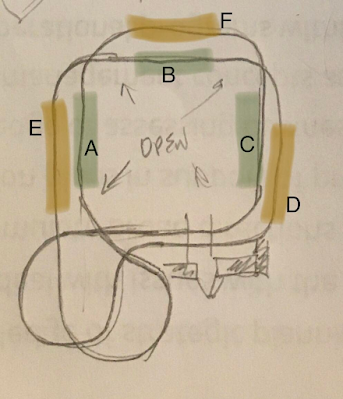

As extra, here's an interesting sketch by Chris Mears who describes it better than me:

I’m fooling around with this a lot. The progression through scenes (green shade) is not ABC..F but AFC-DBE. An alternation so as the train moves through the room it doesn’t move sequentially from wall to wall with half a train still in each wall-scene but like a series of stages so the visible train is only visible on opposite room sides.

|

| Non sequential scenes (credit: Chris Mears) |

But let's stop it for today... more interesting thoughts to share in a next installment!

No comments:

Post a Comment